| Pachanga | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | Son montuno, merengue |

| Cultural origins | Cuba, 1959 |

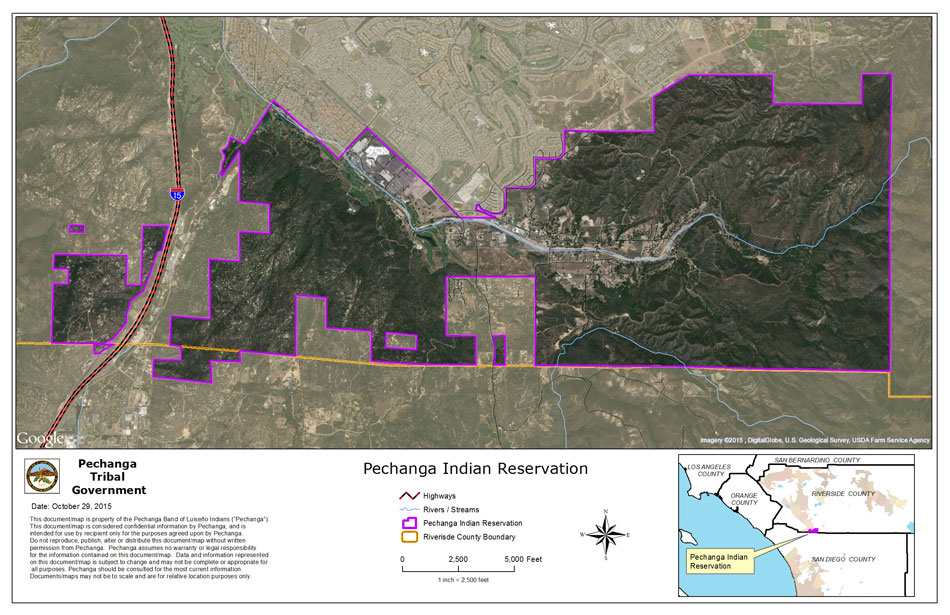

The Pechanga Resort & Casino is a Native American casino on the Pechanga Indian Reservation adjacent to the city of Temecula, California.Pechanga Resort & Casino is the largest casino in the state of California, with over 4,500 slot machines and approximately 200,000 sq ft (19,000 m 2) of gaming space.

| Music of Cuba | |

|---|---|

| General topics | |

| Related articles | |

| Genres | |

| |

| Specific forms | |

| Religious music | |

| Traditional music | |

| Media and performance | |

| Music awards | Beny Moré Award |

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | |

| National anthem | La Bayamesa |

| Regional music |

Pachanga is a genre of music which is described as a mixture of son montuno and merengue and has an accompanying signature style of dance. This type of music has a festive, lively style and is marked by jocular, mischievous lyrics. Pachanga originated in Cuba in the 1950s and played an important role in the evolution of Caribbean style music as it is today. Considered a prominent contributor to the eventual rise of salsa, Pachanga itself is an offshoot of Charanga style music.[1] Very similar in sound to Cha-Cha but with a notably stronger down-beat, Pachanga once experienced massive popularity all across the Caribbean and was brought to the United States by Cuban immigrants post World War II. This led to an explosion of Pachanga music in Cuban music clubs that influenced Latin culture in the United States for decades to come.[2]

Music[edit]

Charanga is a type of traditional ensemble that plays Cuban dance music (mostly Danzón, Danzonete, and Cha cha chá) using violin, flute, horns, drums.

126 reviews of Pechanga RV Resort 'Very nice, clean RV resort. We stayed here after a night of wine tasting in Temecula, so much easier than driving all the way back to San Diego after wine tasting. Nice swimming pool, free shuttles to the casino although it's certainly close enough to walk to. Very conveniently located. Buy Pechanga Resort and Casino tickets at Ticketmaster.com. Find Pechanga Resort and Casino venue concert and event schedules, venue information, directions, and seating charts. Pechanga Resort Casino is the largest casino in California with its 188,000 square-foot gaming floor, 5,000 slot machines, 158 table games, 38 poker tables, 20 restaurants and bars, 1,090 hotel rooms and a 25,5000 square-foot spa. Pechanga is located in the city of Temecula in the wine country of southwest Riverside County.

José Fajardo brought the song 'La Pachanga' to New York in the Cuban charanga style. The orquesta, or band, was referred to as charanga, while the accompanying dance was named the pachanga.[3]The similar sound of the words charanga and pachanga has led to the fact that these two notions are often confused. In fact, charanga is a type of orchestration, while pachanga is a musical and dance genre.

Pechanga Reopening

Eduardo Davidson's tune, 'La Pachanga', with rights managed by Peer International (BMI), achieved international recognition in 1961 when it was licensed in three versions sung by Genie Pace on Capitol, by Audrey Arno in a German version on European Decca, and by Hugo and Luigi and their children's chorus. Billboard commented 'A bright new dance craze from the Latins has resulted in these three good recordings, all with interesting and varying treatments.'[4]

Dance[edit]

As a dance, pachanga has been described as 'a happy-go-lucky dance' of Cuban origin with a Charleston flavor due to the double bending and straightening of the knees. It is danced on the downbeat of four-four time to the usual mambo offbeat music characterized by the charanga instrumentation of flutes, violins, and drums.[5]

Steps[edit]

A basic pachanga step consists of a bending and straightening of the knees. Pachanga is a very grounded dance, with the knees never completely straightening and an emphasis on weight and energy going into the ground. Body movement resulting from weight changes follows the footwork. With a bounce originating in the knees, the upper body will rock as body connectivity and posture are maintained. It mimics a basic mambo step in foot placement and weight shift while incorporating a glide on weight transfer instead of a tap. The shift in weight from one foot to the other gives the illusion of gliding, similar to a moonwalk.

Modern Pachanga[edit]

Pachanga dance today is mainly seen incorporated into salsa shines or footwork. “Shines” can refer either to a performance by a group of solo men or women without a partner, or a pause in partnerwork for each dancer to show off before coming back together. The term shine originates from young African American shoe shiners who would dance for money. While it is not a very popular social dance, many salsa dancers incorporate pachanga movements into their choreography, especially in mambo or salsa on-2 routines. Although people traditionally learned pachanga from friends or family in social settings, as it was the only way to learn many Latin styles, instructors have adapted to a Western studio style of teaching.[6]Pachanga is taught all over the world at different salsa events and congresses. As technology increases and economies and societies become increasingly global, the crossover of different cultures becomes easier, including the blending of different dance styles from all over. People worldwide can learn dances such as pachanga, as well as incorporate its movements into styles with which they are already familiar. Popular instructors include the “Mambo King” Eddie Torres, his son Eddie Torres Jr., and his former partner Shani Talmor.

History[edit]

Though Pachanga was created in Cuba, it rose to popularity in the United States in the 1950s during a wave of Cuban immigration. America is where Pachanga truly became popular and known in the public consciousness and developed into the music, dance and overall influence that it is today.[1]

Cuban immigration[edit]

The development of the style of music that came to be known as Salsa in the U.S. in the late 1960s relied heavily on the Latin music scene in New York City and more specifically the South Bronx. In the post World War Two era, New York city experienced a surge of Cuban immigration. During this time Cuba underwent several economic and social crises including the destabilization of international tobacco and sugar markets and civil upheavals that further disrupted the already fragile Cuban republic.[7] As a result, tens of thousands of Cubans migrated to the U.S. hoping to find greater economic opportunities and more civil liberties, establishing sizeable communities in New Orleans, Tampa, and New York City.[8] The start of the Cuban Revolution in 1953 only gave Cuban civilians more reason to flee the country, adding to the flood of immigrants to the United States.[7]

Rise of Pachanga in New York[edit]

At the time, the South Bronx had large developments of affordable public housing where many Cubans and other Caribbean immigrants ended up finding a place to call home. In addition to housing, the South Bronx also offered a strong infrastructure for the growth of a culturally rich community. The Cuban communities that formed brought with them their own art and culture and in particular they brought with them Cuban music and dance.[9] The Caribbean music scene in New York exploded along with the rise of Caribbean ballrooms, clubs and dance halls. These establishments featured all the popular Caribbean music styles of the era, beginning with the Mambo. The Mambo grew in popularity at an alarming rate sparking “Mambo mania” throughout the U.S. to the point that even mainstream musicians such as Rosemary Clooney and Perry Como were incorporating the sounds of Mambo into their pop music. The success that Mambo had in finding its way into the mainstream paved the way for other forms of Caribbean music to be successful. It wasn't long before everyone in New York was listening and dancing to Pachanga.[10]

Two clubs in particular that are inextricably linked with Pachanga's development and popularity are the Triton After-Hours Club and the Caravana Club. The Bronx's Caravana Club is commonly thought of as the home of Pachanga. Opened in the summer of 1959, the Caravana Club instantly became a major hub for the Latin music scene in New York by presenting major bands every week. The clubs popularity truly rose after the live recording of Charlie Palmieri’s 'Pachanga at the Caravana Club' in 1961 which cemented its reputation as the home of Pachanga. At the Triton Club on the other hand, Johnny Pacheco improvised a dance move known as the “Bronx Hop” which later became a major part of the Pachanga dance fad.

A group of patrons at the Caravana Club even formed a dance group named “Los Pachangueros” that performed across the city. At this time, a Pachanga dance craze had also struck the city with such popularity that countless articles about it made their way into mainstream American publications including The New York Times, El Diario and the specialized Ballroom Dance Magazine.[11]

References[edit]

- ^ abMoore, Robin (2001). 'Revolucion con Pachanga? Dance Music in Socialist Cuba'. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies. Vol. 26, No. 52, pp. 151-177

- ^Peter Manuel (May 1987). 'Marxism, Nationalism and Popular Music in Revolutionary Cuba', pp. 161-178. Popular Music Vol. 6, No. 2. ISSN0261-1430. JSTOR853419.

- ^Salazar, Max (August 1998). 'Joe Quijano: la Pachanga se baila así'. Latin Beat Magazine. 8: 22–23 – via World Scholar: Latin America and the Caribbean Portal.

- ^Billboard, 20 March 1961, p. 99

- ^White, Betty (1962). Ballroom DanceBook for Teachers. David McKay Company, Inc., p. 327. Library of Congress Number 62-18465

- ^McMains, Juliet E. (2015). Spinning Mambo Into Salsa: Caribbean Dance in Global Commerce. Oxford University Press. ISBN9780199324644.

- ^ abDuany, George (2017). Cuban Migration: A Post Revolution Exodus Ebbs and Flows. Migration Policy Institute

- ^Perez, Lisandro (1986). Cubans in the United States. American Academy of Political and Social Science

- ^Lao-Montes, A.; Davila, A.(2001). Mambo Montage: The Latinization of New York Columbia University Press, New York

- ^Hutchinson, S.(2004). Mambo on 2: The Birth of a New Dance in New York City pp. 108-136, Centro Journal, vol. 10

- ^Singer, Roberta A.; Martinez, Elena (2004). A South Bronx Latin Music Tale p. 176-203. Centro Journal ISSN 1538-6279

External links[edit]

- Video of a pachanga dance lesson by Eddie Torres Jr.

- Video of dance lesson by Killer Jo Piro in a 1961 silent film

- Video of pachanga dance performance by Melissa Rosado at the 2010 Hamburg Salsa Congress in Germany

- Video of Palladium-era dancers dancing pachanga at the 2004 West Coast Salsa Congress

The Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians has called the Temecula valley home for more than 10,000 years. Life on earth began in this valley at ‘Éxva Teméeku, the birthplace of the Káamalam (First Children). Teméeku was the place where the world as we know it came to be: events that took place here determined how some people became plants and animals, how people dealt with sickness and death, why some things could be eaten yet others could not, and all the other details of life in native California.

Pre-Contact (10,000+ Years Ago)

Groups of people now known as Luiseño Indians have inhabited the Temecula Valley for thousands of years. We call ourselves Payómkawichum (the People of the West), and we are made up of seven bands: Pechanga, Pauma, Pala, Rincon, San Luis Rey, La Jolla, and Soboba. Evidence of our presence before the arrival of Europeans survives throughout the valley. Bedrock mortars, stone tools, pottery, and rock art are still found in Riverside and San Diego Counties. These artifacts prove that we have a long history and a rich culture that existed before the arrival of the Spanish Missionaries.

Through periods of plenty, scarcity and adversity, we have governed ourselves and cared for our lands. Over millennia, we came to understand the importance of natural cycles and learned how to manage our resources. We developed a variety of technologies, such as stone-tool manufacture, basket weaving, and pottery making, and our surplus goods were distributed along Southern California’s extensive trade routes.

Our society was organized to ensure that everyone had food and shelter, and everyone was raised to know what was expected of him or her. The stories of how the world was created have been passed down for generations, and these stories contain rules for proper behavior and the consequences of breaking those rules. Before the arrival of Europeans, the Payómkawichum understood their place in their world.

Post-Contact (1797)

The invasion of Spanish Missionaries – and each successive group of non-Natives – to the Temecula Valley had a devastating effect on the Payómkawichum, but we have survived every challenge. Generation after generation, we have grown and adapted to meet changing times and conditions. This land is witness to our story.

The Missionaries (1797-1834)

Europeans first arrived in the Temecula Valley in 1797. Father Juan Norberto de Santiago, a Franciscan priest, records passing through the Temecula Valley during an exploratory journey to identify possible sites for future missions. In 1798, the Spanish missionaries established Mission San Luis Rey de Francia within the borders of Luiseño Ancestral Territory. The Payómkawichum began to be called San Luiseños, and later, just Luiseños.

Life in the mission was hard for the Payómkawichum. Our ancestors were fed European foods that were not as nutritious as the fresh native foods they had eaten before. The poor diet, combined with new diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza, caused many Native people to get sick. Within a few decades of the founding of Mission San Luis Rey, several thousand Payómkawichum had died. Many of those who caught these diseases never lived at the mission, but they got sick from friends and relatives who had visited them.

The deaths of so many, combined with a strict social structure that separated people by age and gender, almost destroyed our culture. Stories and ceremonies were lost, and the language of the ‘atáaxum (Native people), was only used in secret. By the time the missions were secularized by the Mexican government in 1834, the population of the Payómkawichum has been decimated, and many ‘atáaxum were living in small isolated villages throughout the Temecula Valley. The Natives left behind when the Missions were abandoned returned to these small villages, or in some cases, started new villages of their own.

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and the Temecula Massacre (1847)

While most Payómkawichum did not participate in the Mexican-American war, many of them were directly affected by it. A series of events triggered by the Battle of San Pasqual (1846) led to the Temecula Massacre of 1847. Historical records suggest that the attack was a retaliation for the Pauma Massacre. During the Pauma Massacre, eleven Mexican soldiers who had participated in the Battle of San Pasqual were killed at Warner Hot Springs for stealing horses from the Pauma people.

One day in early January, a troop of Mexican soldiers and their Native accomplices trapped a group of Temecula people in a local canyon and killed many of them. More than one hundred Temecula Indians were killed in the Massacre, but we will never know the exact number. When the Mormon Battalion reached Temecula around January 25, 1847, many of the dead were still unburied, and a massive rainstorm the day before had washed some of the bodies away. The men in the Battalion helped our ancestors bury the remaining dead before continuing their journey to San Diego. Victims of the Temecula Massacre now rest at the Old Temecula Village Cemetery.

The Mexican-American war ended in February 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. California was part of the huge territory that Mexico ceded to the U.S. under the terms of the Treaty. The Treaty specified that Native people in the new U.S. territory were to have the same legal rights they had enjoyed as Mexican citizens; instead, the U.S. government chose to withhold citizenship from Native Californians, and as a result, most of them lost their right to own property, too.

California Statehood (1850) and the Treaty of Temecula (1852)

One of the unfortunate effects of statehood on California’s Native people was the passing of An Act for the Governance and Protection of Indians on April 22, 1850. This Act and its 1860 Amendments permitted American citizens “to have the care, custody, control and earnings of such [Indian] minor until he or she obtain the age of majority.' The later amendments allowed adult Indians to be “indentured” (enslaved) in the same way. Though the Act of 1850 was intended to keep homeless Indians off the streets, unscrupulous people used it as an excuse to kidnap ‘atáaxum and sell them to unaware or uncaring masters.

Shortly after California became a state, U.S. Indian agents came to the Temecula Valley to “make peace” with the ‘atáaxum here. The Treaty of Temecula was one of 18 unratified treaties signed by representatives of nearly 200 California tribes throughout the state. Ysidro Toshovwul and Lauriano Cahparahpish are Pechanga ancestors who signed the Treaty in 1852.

The treaties ensured that large tracts of land around the state would be reserved for the sole use of the Native groups to whom they belonged (with the exception of mineral rights and public roads). In return, the government promised to provide a specific amount of livestock and goods. However, the U.S. Senate refused to ratify any of the treaties and the original documents were considered “lost” until 1905. By the time the unratified treaties were rediscovered, most of the reservations in and near Temecula had already been established and inhabited for decades, and the original agreements were no longer valid.

The Temecula Eviction (1875)

A group of Temecula Valley ranchers petitioned the San Francisco District Court for permission to evict the Payómkawichum who lived in the village on the Little Temecula Rancho. The judge agreed to the eviction, ignoring the fact that our ancestors had lived there for generations under the terms of a Mexican land grant. The eviction took place between September 20 and 23, 1875. José Gonzales, Juan Murrieta, Louis Wolf, and several other local landowners formed an armed posse, assisted by Sherriff Hunsaker of San Diego. The posse members loaded the contents of each home into wagons and dumped everything about three miles to the south, forcing the Indians to follow the wagons on foot.

Despite losing nearly everything they owned, the Temecula people found ways to survive. At first, the evictees stayed on John Magee’s land, close to the place where the posse had driven them. Magee was married to a Temecula Indian woman named Custoria Nesecat, and he was sympathetic to the ‘atáaxum. Later, most of our ancestors moved upstream to a small, secluded valley near a spring called Pecháa'a (from pechaq = to drip). This spring is where the Pechanga band gets its name: Pecháa’anga means 'at Pechaa'a; at the place where water drips.' (Click here for more information about the Temecula Eviction.)

Creation of the Reservation (1882)

On June 27, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Executive Order that established the Pechanga Indian Reservation. The reservation’s name comes from the place where the Temecula Indians settled after they were evicted from the village at Little Temecula.

The Pechanga Resort & Casino is a Native American casino on the Pechanga Indian Reservation adjacent to the city of Temecula, California.Pechanga Resort & Casino is the largest casino in the state of California, with over 4,500 slot machines and approximately 200,000 sq ft (19,000 m 2) of gaming space.

| Music of Cuba | |

|---|---|

| General topics | |

| Related articles | |

| Genres | |

| |

| Specific forms | |

| Religious music | |

| Traditional music | |

| Media and performance | |

| Music awards | Beny Moré Award |

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | |

| National anthem | La Bayamesa |

| Regional music |

Pachanga is a genre of music which is described as a mixture of son montuno and merengue and has an accompanying signature style of dance. This type of music has a festive, lively style and is marked by jocular, mischievous lyrics. Pachanga originated in Cuba in the 1950s and played an important role in the evolution of Caribbean style music as it is today. Considered a prominent contributor to the eventual rise of salsa, Pachanga itself is an offshoot of Charanga style music.[1] Very similar in sound to Cha-Cha but with a notably stronger down-beat, Pachanga once experienced massive popularity all across the Caribbean and was brought to the United States by Cuban immigrants post World War II. This led to an explosion of Pachanga music in Cuban music clubs that influenced Latin culture in the United States for decades to come.[2]

Music[edit]

Charanga is a type of traditional ensemble that plays Cuban dance music (mostly Danzón, Danzonete, and Cha cha chá) using violin, flute, horns, drums.

126 reviews of Pechanga RV Resort 'Very nice, clean RV resort. We stayed here after a night of wine tasting in Temecula, so much easier than driving all the way back to San Diego after wine tasting. Nice swimming pool, free shuttles to the casino although it's certainly close enough to walk to. Very conveniently located. Buy Pechanga Resort and Casino tickets at Ticketmaster.com. Find Pechanga Resort and Casino venue concert and event schedules, venue information, directions, and seating charts. Pechanga Resort Casino is the largest casino in California with its 188,000 square-foot gaming floor, 5,000 slot machines, 158 table games, 38 poker tables, 20 restaurants and bars, 1,090 hotel rooms and a 25,5000 square-foot spa. Pechanga is located in the city of Temecula in the wine country of southwest Riverside County.

José Fajardo brought the song 'La Pachanga' to New York in the Cuban charanga style. The orquesta, or band, was referred to as charanga, while the accompanying dance was named the pachanga.[3]The similar sound of the words charanga and pachanga has led to the fact that these two notions are often confused. In fact, charanga is a type of orchestration, while pachanga is a musical and dance genre.

Pechanga Reopening

Eduardo Davidson's tune, 'La Pachanga', with rights managed by Peer International (BMI), achieved international recognition in 1961 when it was licensed in three versions sung by Genie Pace on Capitol, by Audrey Arno in a German version on European Decca, and by Hugo and Luigi and their children's chorus. Billboard commented 'A bright new dance craze from the Latins has resulted in these three good recordings, all with interesting and varying treatments.'[4]

Dance[edit]

As a dance, pachanga has been described as 'a happy-go-lucky dance' of Cuban origin with a Charleston flavor due to the double bending and straightening of the knees. It is danced on the downbeat of four-four time to the usual mambo offbeat music characterized by the charanga instrumentation of flutes, violins, and drums.[5]

Steps[edit]

A basic pachanga step consists of a bending and straightening of the knees. Pachanga is a very grounded dance, with the knees never completely straightening and an emphasis on weight and energy going into the ground. Body movement resulting from weight changes follows the footwork. With a bounce originating in the knees, the upper body will rock as body connectivity and posture are maintained. It mimics a basic mambo step in foot placement and weight shift while incorporating a glide on weight transfer instead of a tap. The shift in weight from one foot to the other gives the illusion of gliding, similar to a moonwalk.

Modern Pachanga[edit]

Pachanga dance today is mainly seen incorporated into salsa shines or footwork. “Shines” can refer either to a performance by a group of solo men or women without a partner, or a pause in partnerwork for each dancer to show off before coming back together. The term shine originates from young African American shoe shiners who would dance for money. While it is not a very popular social dance, many salsa dancers incorporate pachanga movements into their choreography, especially in mambo or salsa on-2 routines. Although people traditionally learned pachanga from friends or family in social settings, as it was the only way to learn many Latin styles, instructors have adapted to a Western studio style of teaching.[6]Pachanga is taught all over the world at different salsa events and congresses. As technology increases and economies and societies become increasingly global, the crossover of different cultures becomes easier, including the blending of different dance styles from all over. People worldwide can learn dances such as pachanga, as well as incorporate its movements into styles with which they are already familiar. Popular instructors include the “Mambo King” Eddie Torres, his son Eddie Torres Jr., and his former partner Shani Talmor.

History[edit]

Though Pachanga was created in Cuba, it rose to popularity in the United States in the 1950s during a wave of Cuban immigration. America is where Pachanga truly became popular and known in the public consciousness and developed into the music, dance and overall influence that it is today.[1]

Cuban immigration[edit]

The development of the style of music that came to be known as Salsa in the U.S. in the late 1960s relied heavily on the Latin music scene in New York City and more specifically the South Bronx. In the post World War Two era, New York city experienced a surge of Cuban immigration. During this time Cuba underwent several economic and social crises including the destabilization of international tobacco and sugar markets and civil upheavals that further disrupted the already fragile Cuban republic.[7] As a result, tens of thousands of Cubans migrated to the U.S. hoping to find greater economic opportunities and more civil liberties, establishing sizeable communities in New Orleans, Tampa, and New York City.[8] The start of the Cuban Revolution in 1953 only gave Cuban civilians more reason to flee the country, adding to the flood of immigrants to the United States.[7]

Rise of Pachanga in New York[edit]

At the time, the South Bronx had large developments of affordable public housing where many Cubans and other Caribbean immigrants ended up finding a place to call home. In addition to housing, the South Bronx also offered a strong infrastructure for the growth of a culturally rich community. The Cuban communities that formed brought with them their own art and culture and in particular they brought with them Cuban music and dance.[9] The Caribbean music scene in New York exploded along with the rise of Caribbean ballrooms, clubs and dance halls. These establishments featured all the popular Caribbean music styles of the era, beginning with the Mambo. The Mambo grew in popularity at an alarming rate sparking “Mambo mania” throughout the U.S. to the point that even mainstream musicians such as Rosemary Clooney and Perry Como were incorporating the sounds of Mambo into their pop music. The success that Mambo had in finding its way into the mainstream paved the way for other forms of Caribbean music to be successful. It wasn't long before everyone in New York was listening and dancing to Pachanga.[10]

Two clubs in particular that are inextricably linked with Pachanga's development and popularity are the Triton After-Hours Club and the Caravana Club. The Bronx's Caravana Club is commonly thought of as the home of Pachanga. Opened in the summer of 1959, the Caravana Club instantly became a major hub for the Latin music scene in New York by presenting major bands every week. The clubs popularity truly rose after the live recording of Charlie Palmieri’s 'Pachanga at the Caravana Club' in 1961 which cemented its reputation as the home of Pachanga. At the Triton Club on the other hand, Johnny Pacheco improvised a dance move known as the “Bronx Hop” which later became a major part of the Pachanga dance fad.

A group of patrons at the Caravana Club even formed a dance group named “Los Pachangueros” that performed across the city. At this time, a Pachanga dance craze had also struck the city with such popularity that countless articles about it made their way into mainstream American publications including The New York Times, El Diario and the specialized Ballroom Dance Magazine.[11]

References[edit]

- ^ abMoore, Robin (2001). 'Revolucion con Pachanga? Dance Music in Socialist Cuba'. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies. Vol. 26, No. 52, pp. 151-177

- ^Peter Manuel (May 1987). 'Marxism, Nationalism and Popular Music in Revolutionary Cuba', pp. 161-178. Popular Music Vol. 6, No. 2. ISSN0261-1430. JSTOR853419.

- ^Salazar, Max (August 1998). 'Joe Quijano: la Pachanga se baila así'. Latin Beat Magazine. 8: 22–23 – via World Scholar: Latin America and the Caribbean Portal.

- ^Billboard, 20 March 1961, p. 99

- ^White, Betty (1962). Ballroom DanceBook for Teachers. David McKay Company, Inc., p. 327. Library of Congress Number 62-18465

- ^McMains, Juliet E. (2015). Spinning Mambo Into Salsa: Caribbean Dance in Global Commerce. Oxford University Press. ISBN9780199324644.

- ^ abDuany, George (2017). Cuban Migration: A Post Revolution Exodus Ebbs and Flows. Migration Policy Institute

- ^Perez, Lisandro (1986). Cubans in the United States. American Academy of Political and Social Science

- ^Lao-Montes, A.; Davila, A.(2001). Mambo Montage: The Latinization of New York Columbia University Press, New York

- ^Hutchinson, S.(2004). Mambo on 2: The Birth of a New Dance in New York City pp. 108-136, Centro Journal, vol. 10

- ^Singer, Roberta A.; Martinez, Elena (2004). A South Bronx Latin Music Tale p. 176-203. Centro Journal ISSN 1538-6279

External links[edit]

- Video of a pachanga dance lesson by Eddie Torres Jr.

- Video of dance lesson by Killer Jo Piro in a 1961 silent film

- Video of pachanga dance performance by Melissa Rosado at the 2010 Hamburg Salsa Congress in Germany

- Video of Palladium-era dancers dancing pachanga at the 2004 West Coast Salsa Congress

The Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians has called the Temecula valley home for more than 10,000 years. Life on earth began in this valley at ‘Éxva Teméeku, the birthplace of the Káamalam (First Children). Teméeku was the place where the world as we know it came to be: events that took place here determined how some people became plants and animals, how people dealt with sickness and death, why some things could be eaten yet others could not, and all the other details of life in native California.

Pre-Contact (10,000+ Years Ago)

Groups of people now known as Luiseño Indians have inhabited the Temecula Valley for thousands of years. We call ourselves Payómkawichum (the People of the West), and we are made up of seven bands: Pechanga, Pauma, Pala, Rincon, San Luis Rey, La Jolla, and Soboba. Evidence of our presence before the arrival of Europeans survives throughout the valley. Bedrock mortars, stone tools, pottery, and rock art are still found in Riverside and San Diego Counties. These artifacts prove that we have a long history and a rich culture that existed before the arrival of the Spanish Missionaries.

Through periods of plenty, scarcity and adversity, we have governed ourselves and cared for our lands. Over millennia, we came to understand the importance of natural cycles and learned how to manage our resources. We developed a variety of technologies, such as stone-tool manufacture, basket weaving, and pottery making, and our surplus goods were distributed along Southern California’s extensive trade routes.

Our society was organized to ensure that everyone had food and shelter, and everyone was raised to know what was expected of him or her. The stories of how the world was created have been passed down for generations, and these stories contain rules for proper behavior and the consequences of breaking those rules. Before the arrival of Europeans, the Payómkawichum understood their place in their world.

Post-Contact (1797)

The invasion of Spanish Missionaries – and each successive group of non-Natives – to the Temecula Valley had a devastating effect on the Payómkawichum, but we have survived every challenge. Generation after generation, we have grown and adapted to meet changing times and conditions. This land is witness to our story.

The Missionaries (1797-1834)

Europeans first arrived in the Temecula Valley in 1797. Father Juan Norberto de Santiago, a Franciscan priest, records passing through the Temecula Valley during an exploratory journey to identify possible sites for future missions. In 1798, the Spanish missionaries established Mission San Luis Rey de Francia within the borders of Luiseño Ancestral Territory. The Payómkawichum began to be called San Luiseños, and later, just Luiseños.

Life in the mission was hard for the Payómkawichum. Our ancestors were fed European foods that were not as nutritious as the fresh native foods they had eaten before. The poor diet, combined with new diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza, caused many Native people to get sick. Within a few decades of the founding of Mission San Luis Rey, several thousand Payómkawichum had died. Many of those who caught these diseases never lived at the mission, but they got sick from friends and relatives who had visited them.

The deaths of so many, combined with a strict social structure that separated people by age and gender, almost destroyed our culture. Stories and ceremonies were lost, and the language of the ‘atáaxum (Native people), was only used in secret. By the time the missions were secularized by the Mexican government in 1834, the population of the Payómkawichum has been decimated, and many ‘atáaxum were living in small isolated villages throughout the Temecula Valley. The Natives left behind when the Missions were abandoned returned to these small villages, or in some cases, started new villages of their own.

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and the Temecula Massacre (1847)

While most Payómkawichum did not participate in the Mexican-American war, many of them were directly affected by it. A series of events triggered by the Battle of San Pasqual (1846) led to the Temecula Massacre of 1847. Historical records suggest that the attack was a retaliation for the Pauma Massacre. During the Pauma Massacre, eleven Mexican soldiers who had participated in the Battle of San Pasqual were killed at Warner Hot Springs for stealing horses from the Pauma people.

One day in early January, a troop of Mexican soldiers and their Native accomplices trapped a group of Temecula people in a local canyon and killed many of them. More than one hundred Temecula Indians were killed in the Massacre, but we will never know the exact number. When the Mormon Battalion reached Temecula around January 25, 1847, many of the dead were still unburied, and a massive rainstorm the day before had washed some of the bodies away. The men in the Battalion helped our ancestors bury the remaining dead before continuing their journey to San Diego. Victims of the Temecula Massacre now rest at the Old Temecula Village Cemetery.

The Mexican-American war ended in February 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. California was part of the huge territory that Mexico ceded to the U.S. under the terms of the Treaty. The Treaty specified that Native people in the new U.S. territory were to have the same legal rights they had enjoyed as Mexican citizens; instead, the U.S. government chose to withhold citizenship from Native Californians, and as a result, most of them lost their right to own property, too.

California Statehood (1850) and the Treaty of Temecula (1852)

One of the unfortunate effects of statehood on California’s Native people was the passing of An Act for the Governance and Protection of Indians on April 22, 1850. This Act and its 1860 Amendments permitted American citizens “to have the care, custody, control and earnings of such [Indian] minor until he or she obtain the age of majority.' The later amendments allowed adult Indians to be “indentured” (enslaved) in the same way. Though the Act of 1850 was intended to keep homeless Indians off the streets, unscrupulous people used it as an excuse to kidnap ‘atáaxum and sell them to unaware or uncaring masters.

Shortly after California became a state, U.S. Indian agents came to the Temecula Valley to “make peace” with the ‘atáaxum here. The Treaty of Temecula was one of 18 unratified treaties signed by representatives of nearly 200 California tribes throughout the state. Ysidro Toshovwul and Lauriano Cahparahpish are Pechanga ancestors who signed the Treaty in 1852.

The treaties ensured that large tracts of land around the state would be reserved for the sole use of the Native groups to whom they belonged (with the exception of mineral rights and public roads). In return, the government promised to provide a specific amount of livestock and goods. However, the U.S. Senate refused to ratify any of the treaties and the original documents were considered “lost” until 1905. By the time the unratified treaties were rediscovered, most of the reservations in and near Temecula had already been established and inhabited for decades, and the original agreements were no longer valid.

The Temecula Eviction (1875)

A group of Temecula Valley ranchers petitioned the San Francisco District Court for permission to evict the Payómkawichum who lived in the village on the Little Temecula Rancho. The judge agreed to the eviction, ignoring the fact that our ancestors had lived there for generations under the terms of a Mexican land grant. The eviction took place between September 20 and 23, 1875. José Gonzales, Juan Murrieta, Louis Wolf, and several other local landowners formed an armed posse, assisted by Sherriff Hunsaker of San Diego. The posse members loaded the contents of each home into wagons and dumped everything about three miles to the south, forcing the Indians to follow the wagons on foot.

Despite losing nearly everything they owned, the Temecula people found ways to survive. At first, the evictees stayed on John Magee’s land, close to the place where the posse had driven them. Magee was married to a Temecula Indian woman named Custoria Nesecat, and he was sympathetic to the ‘atáaxum. Later, most of our ancestors moved upstream to a small, secluded valley near a spring called Pecháa'a (from pechaq = to drip). This spring is where the Pechanga band gets its name: Pecháa’anga means 'at Pechaa'a; at the place where water drips.' (Click here for more information about the Temecula Eviction.)

Creation of the Reservation (1882)

On June 27, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Executive Order that established the Pechanga Indian Reservation. The reservation’s name comes from the place where the Temecula Indians settled after they were evicted from the village at Little Temecula.

Author Helen Hunt Jackson was instrumental in securing reservation land for the Pechanga people. She visited Temecula shortly after the Eviction. At that time, Jackson was a U.S. government agent investigating the living conditions of Southern California Indians. She included several first-hand accounts of the Eviction in her report, which helped sway government opinion in favor of our people.

Pechanga Casino Hotel

The Kelsey Tract (1907)

Though life on Pechanga Reservation seemed to start well for the Pechanga people, a series of droughts and setbacks left them on the brink of starvation in the early 1900s. Most of our ancestors had to find work off the reservation to survive. Many of them found work on local ranches and farms as cowboys, field hands, and servants. Vail Ranch, in particular, hired a significant number of ‘atáaxum from the Pechanga, Pala, Rincon, Soboba, and Cahuilla reservations.

In 1906, U.S. Indian Commissioner C.E. Kelsey suggested that the reservation needed additional farmland if our ancestors were going to survive. In 1907, the U.S. government purchased 235 acres of land next to Pechanga Reservation that came to be known as the Kelsey Tract. Despite the nearby spring (called Túuchaana), there wasn’t enough water to irrigate the entire property reliably. To make improve the water supply, the Pechanga people dug a well and installed a windmill-powered pump. The land was put into trust for Pechanga under the U.S. Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

The Mission Indian Federation (1919) and U.S. Indian Termination Policies (1953 – 1964)

The Mission Indian Federation (MIF) was the first Native American Civil Rights group founded and operated by Southern California Indians. Membership was open to everyone, though only Native people could vote on resolutions. The MIF’s primary goals were freedom from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and full citizenship rights for all Native Americans. Many Pechaángayam were active members of the organization, and some held leadership positions in the organization, including Eduardo Garcia, Antonio Ashman, and Dan Pico.

The MIF fought for Indian Civil Rights for over fifty years. The organization was at its height when the Indian Citizenship Act was passed on June 2, 1924. However, this Act did not affect all ‘atáaxum equally, so the MIF was still active in Southern California through the 1950s and 1960s, particularly during the U.S. Government’s Indian Termination Policy period. The Mission Indian Federation finally dissolved in the early 1970s. (Click here for more information about the Mission Indian Federation.)

During the 1950s and 1960s, the United States created several laws that have come to be known as the Indian Termination Policies. These laws effectively forced the assimilation of over 100 formerly recognized Native American tribes by closing their reservations and cutting them off from the services they had received through the federal government. The government believed the closures were justified because a 1943 Senate report stated that living conditions on many reservations were so poor that forcing Indians to become part of mainstream America could only be an improvement. The Indian Termination Era officially ended with the passage of the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968 and the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, but many California Natives are still effected by the laws made during Termination.

The Pechanga tribe was never slated for Termination, but they were affected by Public Law (PL) 280, which was passed in 1953 during the Termination era. Promoted as a way to reduce BIA presence on Indian reservations, PL 280 placed reservation Indians under state jurisdiction for most criminal and some civil offenses while reducing their access to federal services. Though PL 280 has been amended many times, it still affects people living on California reservations today.

Pechanga Hotel

Pechanga Today (1988 – present)

Morongo

The last thirty years have brought many changes to the lives of the Pechaángayam. The Indian Gaming Acts of 1988, 1998, and 2000 gave tribes in California the right to open gaming facilities on their lands. In 1995, Pechanga opened its first gaming facility, which has expanded over the last twenty years to include a hotel, spa, and golf course. Pechanga’s gaming operations and related investments have allowed us to provide our people with more opportunities than they have had in the past, including better healthcare and access to higher education.

Www.pechanga.com

In 1988, the passage of the Southern California Indian Land Transfer (Public Law 100-581) Act added 303 acres along Pechanga's northern boundary. The addition of the Great Oak Ranch property in 2003 and the purchase of Pu’éska Mountain in 2012 expanded the reservation further. Today, the gross total land area of Pechanga Reservation stands at 7,080 acres. Our ancestral territory extends across the borders of Riverside and San Diego counties, and we have a responsibility to preserve and protect this land . Today, Tribal Government operations such as Pechanga's monitor programs and cultural resource management exist to fully honor and protect the land and our cultural sites.

Pechanga Casino Open

Indian Gaming in the Temecula Valley has not only helped to improve the lives of Pechanga people, but also our local community. The casino at Pechanga employs thousands of local people and generates millions of dollars in tax revenue every year. The tribe actively donates money to local charities and public works projects. Most recently, we collaborated with the people of the Temecula Valley to fight the Liberty Quarry development. The project would have destroyed Wexéwxi Pu’éska (Pu’éska Mountain), a very sacred place in the Luiseño religion, and it would have created a lot of air pollution in the valley. After a five-year battle, we purchased the mountain, so both it and the people of the valley are safe from the damage the proposed quarry would have caused. ( Click here for more information about Pu’éska Mountain.)

We, the Pechaángayam, are optimistic about the future. We will continue to help our people and the communities of the Temecula Valley remain self-sufficient and forward thinking for many years to come.